作者介紹

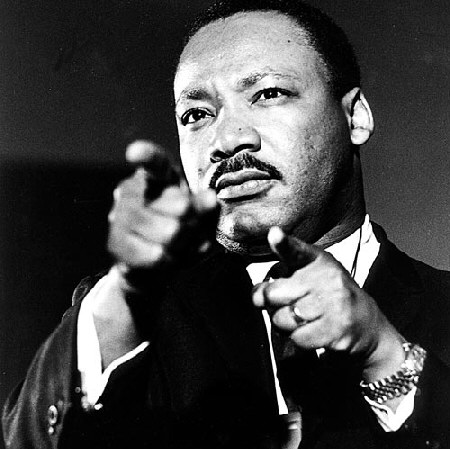

馬丁·路德·金(Martin Luther King, Jr.),1929年1月15日—1968年4月4日),著名的美國民權運動領袖,1964年度諾貝爾和平獎獲得者,有金牧師之稱。

1929年1月15日馬丁·路德·金出生於喬治亞州的亞特蘭大市奧本街501號,一幢維多利亞式的小樓里。他的父親是教會牧師,母親是教師。15歲時聰穎好學的金以優異成績進入摩爾豪斯學院攻讀社會學,後獲得文學學士學位(1948年馬丁·路德·金獲得莫爾豪斯大學學士學位)。1951年他又獲得柯羅澤神學院學士學位,1955年他從波士頓大學獲得神學博士學位。

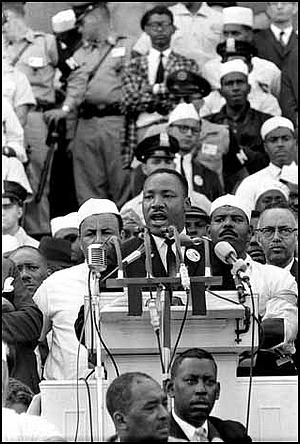

1954年馬丁·路德·金成為阿拉巴馬州蒙哥馬利市的德克斯特大街浸信會教堂(Dexter Avenue Baptist Church)的一位牧師。1955年12月1日,一位名叫做羅沙·帕克斯的黑人婦女在公共汽車上拒絕給白人讓座位,因而被蒙哥馬利節警察當局的當地警員以違反公共汽車座位隔離條令為由逮捕了她。馬丁·路德·金立即組織了蒙哥馬利罷車運動(蒙哥馬利市政改進協會),號召全市近5萬名黑人對公共法與公司進行長達1年的抵制,迫使法院判決取消地方運輸工具上的座位隔離。從此他成為民權運動的領袖人物。1958年他因流浪罪被逮捕。1963年金組織了爭取黑人工作機會和自由權的華盛頓遊行。1964年,他被授予諾貝爾和平獎。1968年4月4日,他在旅館的陽台被一名種族分子刺客開槍正中喉嚨致死。

1986年1月,總統隆納·雷根簽署法令,規定每年一月份的第三個星期一為美國的馬丁·路德·金全國紀念日以紀念這位偉人,並且訂為法定假日。迄今為止美國只有三個以個人紀念日為法定假日的例子,分別為紀念發現美洲大陸的哥倫布的Columbus Day (十月第二個星期一), 紀念喬治·華盛頓的Presidents' Day(二月第三個星期一),與此處所提到的馬丁·路德·金紀念日。他最有影響力且最為人知的一場演講是1963年8月28日的《我有一個夢想》,迫使美國國會在1964年通過《民權法案》宣布種族隔離和種族歧視政策為非法政策。

他的妻子是科麗塔·斯科特·金。

馬丁·路德·金為黑人謀求平等,發動了美國的民權運動,功績卓著,聞名於世。金在成為民權運動積極分子之前,是黑人社區必有的浸禮會的牧師。民權運動是美國黑人教會的產物,本文記敘金的第一次民權演說,揭示了民權運動與黑人教會的關係。

正文

Five score years ago, a great American, in whose symbolic shadow we stand today, signed the Emancipation Proclamation. This momentous decree came as a great beacon light of hope to millions of Negro slaves who had been seared in the flames of withering injustice. It came as a joyous daybreak to end the long night of captivity. But one hundred years later, we must face the tragic fact that the Negro is still not free.

One hundred years later, the life of the Negro is still sadly crippled by the manacles of segregation and the chains of discrimination. One hundred years later, the Negro lives on a lonely island of poverty in the midst of a vast ocean of material prosperity. One hundred years later, the Negro is still languishing in the corners of American society and finds himself an exile in his own land.

So we have come here today to dramatize an appalling condition. In a sense we have come to our nation's capital to cash a check. When the architects of our republic wrote the magnificent words of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence, they were signing a promissory note to which every American was to fall heir.

This note was a promise that all men would be guaranteed the inalienable rights of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. It is obvious today that America has defaulted on this promissory note insofar as her citizens of color are concerned. Instead of honoring this sacred obligation, America has given the Negro people a bad check which has come back marked "insufficient funds." But we refuse to believe that the bank of justice is bankrupt. We refuse to believe that there are insufficient funds in the great vaults of opportunity of this nation.

So we have come to cash this check -- a check that will give us upon demand the riches of freedom and the security of justice. We have also come to this hallowed spot to remind America of the fierce urgency of now. This is no time to engage in the luxury of cooling off or to take the tranquilizing drug of gradualism. Now is the time to rise from the dark and desolate valley of segregation to the sunlit path of racial justice. Now is the time to open the doors of opportunity to all of God's children. Now is the time to lift our nation from the quicksands of racial injustice to the solid rock of brotherhood.

It would be fatal for the nation to overlook the urgency of the moment and to underestimate the determination of the Negro. This sweltering summer of the Negro's legitimate discontent will not pass until there is an invigorating autumn of freedom and equality. Nineteen sixty-three is not an end, but a beginning. Those who hope that the Negro needed to blow off steam and will now be content will have a rude awakening if the nation returns to business as usual. There will be neither rest nor tranquility in America until the Negro is granted his citizenship rights.

The whirlwinds of revolt will continue to shake the foundations of our nation until the bright day of justice emerges. But there is something that I must say to my people who stand on the warm threshold which leads into the palace of justice. In the process of gaining our rightful place we must not be guilty of wrongful deeds. Let us not seek to satisfy our thirst for freedom by drinking from the cup of bitterness and hatred.

We must forever conduct our struggle on the high plane of dignity and discipline. we must not allow our creative protest to degenerate into physical violence. Again and again we must rise to the majestic heights of meeting physical force with soul force.

The marvelous new militancy which has engulfed the Negro community must not lead us to distrust of all white people, for many of our white brothers, as evidenced by their presence here today, have come to realize that their destiny is tied up with our destiny and their freedom is inextricably bound to our freedom.

We cannot walk alone. And as we walk, we must make the pledge that we shall march ahead. We cannot turn back. There are those who are asking the devotees of civil rights, "When will you be satisfied?" we can never be satisfied as long as our bodies, heavy with the fatigue of travel, cannot gain lodging in the motels of the highways and the hotels of the cities. We cannot be satisfied as long as the Negro's basic mobility is from a smaller ghetto to a larger one. We can never be satisfied as long as a Negro in Mississippi cannot vote and a Negro in New York believes he has nothing for which to vote. No, no, we are not satisfied, and we will not be satisfied until justice rolls down like waters and righteousness like a mighty stream.

I am not unmindful that some of you have come here out of great trials and tribulations. Some of you have come fresh from narrow cells. Some of you have come from areas where your quest for freedom left you battered by the storms of persecution and staggered by the winds of police brutality. You have been the veterans of creative suffering. Continue to work with the faith that unearned suffering is redemptive.

Go back to Mississippi, go back to Alabama, go back to Georgia, go back to Louisiana, go back to the slums and ghettos of our northern cities, knowing that somehow this situation can and will be changed. Let us not wallow in the valley of despair. I say to you today, my friends, that in spite of the difficulties and frustrations of the moment, I still have a dream. It is a dream deeply rooted in the American dream.

I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed: "We hold these truths to be self-evident: that all men are created equal." I have a dream that one day on the red hills of Georgia the sons of former slaves and the sons of former slaveowners will be able to sit down together at a table of brotherhood. I have a dream that one day even the state of Mississippi, a desert state, sweltering with the heat of injustice and oppression, will be transformed into an oasis of freedom and justice. I have a dream that my four children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character. I have a dream today.

I have a dream that one day the state of Alabama, whose governor's lips are presently dripping with the words of interposition and nullification, will be transformed into a situation where little black boys and black girls will be able to join hands with little white boys and white girls and walk together as sisters and brothers. I have a dream today. I have a dream that one day every valley shall be exalted, every hill and mountain shall be made low, the rough places will be made plain, and the crooked places will be made straight, and the glory of the Lord shall be revealed, and all flesh shall see it together. This is our hope. This is the faith with which I return to the South. With this faith we will be able to hew out of the mountain of despair a stone of hope. With this faith we will be able to transform the jangling discords of our nation into a beautiful symphony of brotherhood. With this faith we will be able to work together, to pray together, to struggle together, to go to jail together, to stand up for freedom together, knowing that we will be free one day.

This will be the day when all of God's children will be able to sing with a new meaning, "My country, 'tis of thee, sweet land of liberty, of thee I sing. Land where my fathers died, land of the pilgrim's pride, from every mountainside, let freedom ring." And if America is to be a great nation, this must become true. So let freedom ring from the prodigious hilltops of New Hampshire. Let freedom ring from the mighty mountains of New York. Let freedom ring from the heightening Alleghenies of Pennsylvania! Let freedom ring from the snowcapped Rockies of Colorado! Let freedom ring from the curvaceous peaks of California! But not only that; let freedom ring from Stone Mountain of Georgia! Let freedom ring from Lookout Mountain of Tennessee! Let freedom ring from every hill and every molehill of Mississippi. From every mountainside, let freedom ring.

When we let freedom ring, when we let it ring from every village and every hamlet, from every state and every city, we will be able to speed up that day when all of God's children, black men and white men, Jews and Gentiles, Protestants and Catholics, will be able to join hands and sing in the words of the old Negro spiritual, "Free at last! free at last! thank God Almighty, we are free at last!"

譯文:

今天,我高興地同大家一起,參加這次將成為我國歷史上為了爭取自由而舉行的最偉大的示威集會。

100年前,一位偉大的美國人——今天我們就站在他象徵性的身影下——簽署了《解放宣言》。這項重要法令的頒布,對於千百萬灼烤於非正義殘焰中的黑奴,猶如帶來希望之光的碩大燈塔,恰似結束漫漫長夜禁錮的歡暢黎明。

然而,100年後,黑人依然沒有獲得自由。100年後,黑人依然悲慘地蹣跚於種族隔離和種族歧視的枷鎖之下。100年後,黑人依然生活在物質繁榮翰海的貧困孤島上。100年後,黑人依然在美國社會中間向隅而泣,依然感到自己在國土家園中流離漂泊。所以,我們今天來到這裡,要把這駭人聽聞的情況公諸於眾。

從某種意義上說,我們來到國家的首都是為了兌現一張支票。我們共和國的締造者在擬寫憲法和獨立宣言的輝煌篇章時,就簽署了一張每一個美國人都能繼承的期票。這張期票向所有人承諾——不論白人還是黑人——都享有不可讓渡的生存權、自由權和追求幸福權。

然而,今天美國顯然對她的有色公民拖欠著這張期票。美國沒有承兌這筆神聖的債務,而是開始給黑人一張空頭支票——一張蓋著“資金不足”的印戳被退回的支票。但是,我們決不相信正義的銀行會破產。我們決不相信這個國家巨大的機會寶庫會資金不足。 因此,我們來兌現這張支票。這張支票將給我們以寶貴的自由和正義的保障。

我們來到這塊聖地還為了提醒美國:現在正是萬分緊急的時刻。現在不是從容不迫悠然行事或服用漸進主義鎮靜劑的時候。現在是實現民主諾言的時候。現在是走出幽暗荒涼的種族隔離深谷,踏上種族平等的陽關大道的時候。現在是使我們國家走出種族不平等的流沙,踏上充滿手足之情的磐石的時候。現在是使上帝所有孩子真正享有公正的時候。

忽視這一時刻的緊迫性,對於國家將會是致命的。自由平等的朗朗秋日不到來,黑人順情合理哀怨的酷暑就不會過去。1963年不是一個結束,而是一個開端。

如果國家依然我行我素,那些希望黑人只需出出氣就會心滿意足的人將大失所望。在黑人得到公民權之前,美國既不會安寧,也不會平靜。反抗的旋風將繼續震撼我們國家的基石,直至光輝燦爛的正義之日來臨。

但是,對於站在通向正義之宮艱險門檻上的人們,有一些話我必須要說。在我們爭取合法地位的過程中,切不要錯誤行事導致犯罪。我們切不要吞飲仇恨辛酸的苦酒,來解除對於自由的飲渴。

我們應該永遠得體地、紀律嚴明地進行鬥爭。我們不能容許我們富有創造性的抗議淪為暴力行動。我們應該不斷升華到用靈魂力量對付肉體力量的崇高境界。 席捲黑人社會的新的奇蹟般的戰鬥精神,不應導致我們對所有白人的不信任——因為許多白人兄弟已經認識到:他們的命運同我們的命運緊密相連,他們的自由同我們的自由休戚相關。他們今天來到這裡參加集會就是明證。

我們不能單獨行動。當我們行動時,我們必須保證勇往直前。我們不能後退。有人問熱心民權運動的人:“你們什麼時候會感到滿意?”只要黑人依然是不堪形容的警察暴行恐怖的犧牲品,我們就決不會滿意。只要我們在旅途勞頓後,卻被公路旁汽車遊客旅社和城市旅館拒之門外,我們就決不會滿意。只要黑人的基本活動範圍只限於從狹小的黑人居住區到較大的黑人居住區,我們就決不會滿意。只要我們的孩子被“僅供白人”的牌子剝奪個性,損毀尊嚴,我們就決不會滿意。只要密西西比州的黑人不能參加選舉,紐約州的黑人認為他們 與選舉毫不相干,我們就決不會滿意。不,不,我們不會滿意,直至公正似水奔流,正義如泉噴涌。

我並非沒有注意到你們有些人歷盡艱難困苦來到這裡。你們有些人剛剛走出狹小的牢房。有些人來自因追求自由而遭受迫害風暴襲擊和警察暴虐狂飆摧殘的地區。你們飽經風霜,歷盡苦難。繼續努力吧,要相信:無辜受苦終得拯救。 回到密西西比去吧;回到阿拉巴馬去吧;回到南卡羅來納去吧;回到喬治亞去吧;回到路易斯安那去吧;回到我們北方城市中的貧民窟和黑人居住區去吧。要知道,這種情況能夠而且將會改變。我們切不要在絕望的深淵裡沉淪。

朋友們,今天我要對你們說,儘管眼下困難重重,但我依然懷有一個夢。這個夢深深植根於美國夢之中。

我夢想有一天,這個國家將會奮起,實現其立國信條的真諦:“我們認為這些真理不言而喻:人人生而平等。”

我夢想有一天,在喬治亞州的紅色山崗上,昔日奴隸的兒子能夠同昔日奴隸主的兒子同席而坐,親如手足。 我夢想有一天,甚至連密西西比州——一個非正義和壓迫的熱浪逼人的荒漠之州,也會改造成為自由和公正的青青綠洲。

我夢想有一天,我的四個小女兒將生活在一個不是以皮膚的顏色,而是以品格的優劣作為評判標準的國家裡。

我今天懷有一個夢。

我夢想有一天,阿拉巴馬州會有所改變——儘管該州州長現在仍滔滔不絕地說什麼要對聯邦法令提出異議和拒絕執行——在那裡,黑人兒童能夠和白人兒童兄弟姐妹般地攜手並行。

我今天懷有一個夢。

我夢想有一天,深谷彌合,高山夷平,歧路化坦途,曲徑成通衢,上帝的光華再現,普天下生靈共謁。 這是我們的希望。這是我將帶回南方去的信念。有了這個信念,我們就能從絕望之山開採出希望之石。有了這個信念,我們就能把這個國家的嘈雜刺耳的爭吵聲,變為充滿手足之情的悅耳交響曲。有了這個信念,我們就能一同工作,一同祈禱,一同鬥爭,一同入獄,一同維護自由,因為我們知道,我們終有一天會獲得自由。

到了這一天,上帝的所有孩子都能以新的含義高唱這首歌:

我的祖國,可愛的自由之邦,我為您歌唱。這是我祖先終老的地方,這是早期移民自豪的地方,讓自由之聲,響徹每一座山崗。 如果美國要成為偉大的國家,這一點必須實現。因此,讓自由之聲響徹新罕布夏州的巍峨高峰!

讓自由之聲響徹紐約州的崇山峻岭!

讓自由之聲響徹賓夕法尼亞州的阿勒格尼高峰!

讓自由之聲響徹科羅拉多州冰雪皚皚的洛基山!

讓自由之聲響徹加利福尼亞州的婀娜群峰!

不,不僅如此;讓自由之聲響徹喬治亞州的石山!

讓自由之聲響徹田納西州的望山!

讓自由之聲響徹密西西比州的一座座山峰,一個個土丘!

讓自由之聲響徹每一個山崗!

當我們讓自由之聲轟響,當我們讓自由之聲響徹每一個大村小莊,每一個州府城鎮,我們就能加速這一天的到來。那時,上帝的所有孩子,黑人和白人,猶太教徒和非猶太教徒,耶穌教徒和天主教徒,將能攜手同唱那首古老的黑人靈歌:“終於自由了!終於自由了!感謝全能的上帝,我們終於自由了!”

主旨

《我有一個夢》,這是20 世紀最為驚心動魄的聲音之一,穿過近半個世紀的時光隧道,我們仍能感受到其中的大悲憫和大悲痛。但即使在這一場波濤洶湧、黑人的不滿情緒一觸即發的集會上,金博士仍然以他慣有的理性和基督之愛向人群宣講。這就是一個“非暴力”提倡者的理念之花。在他看來,“手段代表了在形成之中的理想和進行之中的目的,人們無法通過邪惡的手段來達到美好的目的。因為手段是種子,目的是樹。”

其它

又稱《在林肯紀念堂前的演講》。《我...》強烈的宣傳、鼓動性強 揭示看演講詞的相關主題。《在...》客觀性,交代了文種,情境場所,增強了文章的莊重氛圍。

馬修連恩在他的歌曲《Heaven's name》的結尾處,曾加入過這段著名演講的最後一段內容。因為兩者的思想是一樣的,就是眾生平等。